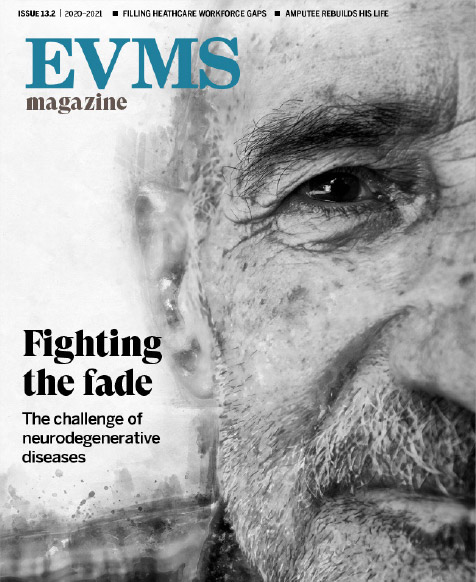

The sometimes blurry world of Alzheimer’s

TO WILLIAM EASON, most people are faceless. No matter the distance, their faces are blurred canvases with water spots of hyper-focused details, none of which he can quite make out.

It’s not that he doesn’t remember people — just that he can’t see enough of their faces to recognize them.

Despite what you may think, the problem is not his eyes.

Mr. Eason has posterior cortical atrophy — or PCA for short. A rare, visual variant of Alzheimer’s disease, it affects areas in the back of the brain responsible for spatial perception, complex visual processing, spelling and calculation.

Navigating his home is difficult. Reading, impossible. Words become jumbled letters, dance on the page or simply vanish. An avid reader, Mr. Eason was devastated by his faltering ability to process what he saw.

“I used to read the newspaper every day from end to end,” he says, “but over the last few years, it has simply become a waste of paper because I can’t see the words.”

This is not what he expected for his retirement years. As a salesman for GE, Mr. Eason traveled the world. He lived in Hong Kong with a spectacular view of the South China Sea. He bought a house 100 feet from the Chesapeake Bay when he retired, so he could awake each morning to the sun rising over the water.

I get up every morning, and there is this beautiful view that I can’t see. In some ways it feels like the world is closed to me.

William Eason

“I get up every morning, and there is this beautiful view that I can’t see,” Mr. Eason says. “In some ways it feels like the world is closed to me.”

His diagnosis of PCA was 10 years in the making. Ten years of bigger type, better glasses and visits to primary care doctors, ophthalmologists and other specialists. Was it from a fall where he hit his head? Was it from a stroke?

No one thought to mention Alzheimer’s until Mr. Eason and his wife Debbie Harrell went to see Mark Flemmer, MD, EVMS Professor of Internal Medicine.

“I felt like we won the lottery,” Mr. Eason says. “He came in with a cadre of doctors, and he listened; he understood, and he was the first to say PCA.”

Mr. Eason was referred to the Memory Consultation Clinic at the EVMS Glennan Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology to confirm the diagnosis.

“It sounds crazy,” he says, “but it was a relief to hear Alzheimer’s because it was good to have a name for it and to understand how to manage that.”

The crime, Ms. Harrell says, is that there aren’t enough support systems and resources readily available.

“The Glennan Center is fabulous, but this area has such a need, and there is still such a stigma around dementia and mental disorders that not enough people talk about it or fund it,” she says. “People think it won’t happen to them.”

Both Mr. Eason and Ms. Harrell hope the new EVMS Lawrence J. Goldrich Institute for Integrated NeuroHealth will align the services and support systems they and other families dealing with neurodegenerative disorders need here in Hampton Roads.

“I studied yoga for seniors, and I was exposed to the power of treating the whole person with diverse multiple healing modalities,” Ms. Harrell said. “It’s thrilling to know there will be this invaluable and desperately needed approach to neurodegenerative disease here at EVMS.”

Also in this issue

Never Miss a Story

The award-winning EVMS Magazine is published four times a year. Subscribe to be notified when the next digital issue is published and/or to receive complimentary copies of the print version.

Subscribe Download a PDF