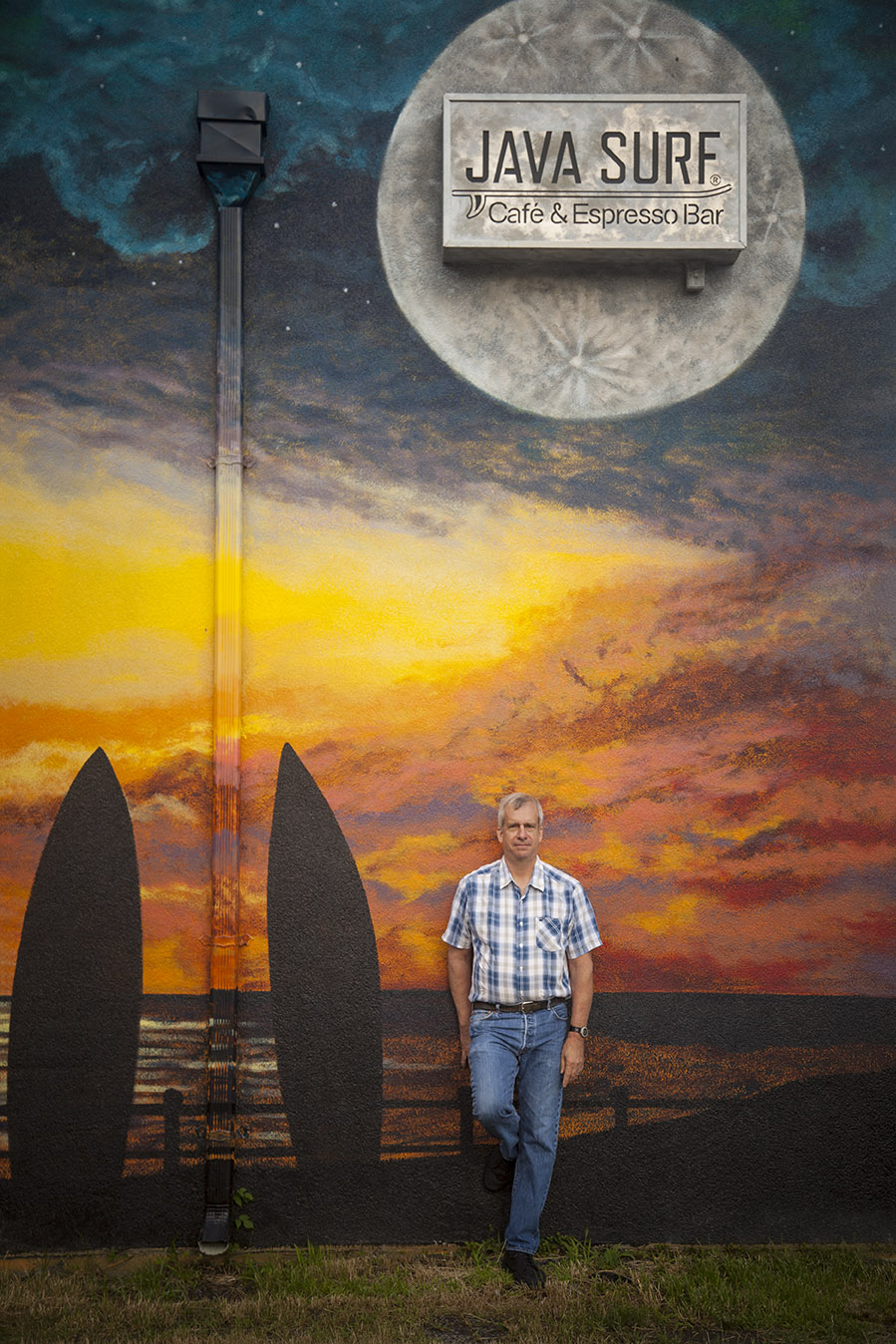

Faculty member starts the morning in a swell way

Frank Lattanzio, PhD, Associate Professor of Physiological Sciences, also serves as Basic Science Director of the Lee Center for Ocular Pharmacology and Director of the Microscopy Facility. He has worked at EVMS for 28 years. When off campus, Dr. Lattanzio can be found surfing early-morning waves — but not in a traditional way.

Describe your unorthodox style: I design and build wooden alaias (uh-lie-yuhs) but surf in a prone position, like bodyboarders do. While unusual here, this type of finless surfboard and riding style originated long ago in Polynesia. Alaias I have built are hanging on the walls as décor in local Java Surf coffee shops.

When do you surf? I live in Deep Creek so I get up at 3:30 a.m. to go to Rudee Inlet in Virginia Beach to be in the water by 5:00. I get about 120 to 150 surfing days annually.

When did you start In New Jersey in 1961. I lived inland and took a train to the ocean. Surfing hadn’t taken off where I lived so I learned on my own. But my favorite place to surf now is right here. I enjoy socializing with other surfers while we wait for waves. Even on small days, it’s never boring.

What benefit do you get from the sport? I love being in the ocean and interacting with something that is not truly under human control. It’s such a pleasure to be out there when the sun comes up, seeing the world reborn again.

What are you most passionate about in your work at EVMS? I am interested in a number of medical areas that seem unrelated — glaucoma, ischemic heart disease and cancer — but share important common threads, such as uncontrolled cellular or vascular growth and aberrations in metabolism and ionic fluxes. My passion is to attempt to understand these commonalities and to then use that information to help resolve these problems.

About Ancient and Modern Alaias

by Frank Lattanzio, PhD

My wooden boards are modern interpretations of alaias, one of the several recognized types of wooden surfing boards used by many of the native peoples of the Pacific and developed to their zenith by the Hawaiians.

The alaias were designed to surf the most challenging and dangerous waves, including Sunset Beach in O’ahu, with the boards normally ranging from 6 to 12 feet in length, 16-20 inches wide and about 1/2 to 1-1/2 inches thick. Alaias could be surfed prone, kneeling or standing and were shaped from a single plank of koa, ulu (breadfruit) or wili-wili (similar to balsa), with the largest ancient alaia collection residing in the Bishop Museum in Honolulu. Nearly all of the surviving boards that were shaped prior to the mid to late-1800s are of koa, possibly because koa, a mahogany-like heavy wood, was most resistant to weathering, rot and surf-related damage than the other, more buoyant woods.

The alaias found in the Bishop Museum collection were originally treated with various preparations to decrease immersion damage, had no fins and were convex in shape across the width of the board, generally having rounded noses, square tails and thin-edged straight rails that were either parallel or ran as a taper from nose to tail.

Starting around 2005, there was a resurgence in making and surfing alaias. Many current surfboard shapers, including Tom and Jon Wegener, have retooled these boards by adding modern style elements, including curved rails and tails, together with concave bottom contours and the use of other woods, especially paulownia, a lightweight, strong wood that is similar to wili-wili but better suited to the marine environment. Alaias are more difficult to surf than modern foam boards, because they lack flotation and fins, which makes them harder to paddle into a wave and more difficult to hold a line. Their appeal to modern surfers resides in their increased planning speed and their ability to slide effortlessly over the face of the wave, as well as allowing modern surfers a chance to recapture skills that were almost lost two centuries ago.

The trend of alaia surfing reached its peak from around 2005 until the early 2010s. It has become more of a niche now because of the difficulty of surfing these boards, especially in comparison with modern surfboards that are easier to paddle and control. The easiest surf breaks to surf alaias are those that have clean wave faces and relatively small, but energetic waves. Surf breaks like Noosa in Australia, the South Shore of Oahu and a number of the California surfbreaks like Cardiff and Malibu are ideal for alaias, but the presence of numerous long boards and stand-up paddleboards at these breaks can make competing for waves on an alaia difficult.

The Hawaiians and especially the Australians have most fully embraced modern alaias and other finless, wooden surfboards. For example, alaias are included as a specific category in Australian surfing competitions. The return to finless surfboards has been described as friction-free surfing by Derek Hynd, an Australian professional surfer that has modified modern foam surfboards into alaia-like surfcraft.

For YouTube videos, search alaia surfing and Derek Hynd surfing, especially the Jefferies Bay (J-Bay) video.

How to build an alaia in 9 steps

by Frank Lattanzio, PhD

- An alaia can be made of any wood that floats, but more buoyant woods like paulownia and cedar are often used. Other options include poplar, mahogany, redwood and basswood. Koa is expensive, difficult to obtain and as heavy as mahogany, while balsa is the most buoyant wood, but also expensive and fragile. Starting thickness of alaia planks can be from 3/4 to 1-½ inches. First, determine the width and length of the board you want to make. Paipo boards, the ancestors of bodyboards, are often less than 4 feet long, while prone alaias run 5-6 feet and stand-up alaias 6-7 feet or more.

- To obtain a blank width of 16-20 inches often requires gluing several long, narrow pieces together using a water-resistant glue (Titebond 3™ or a marine grade epoxy), although poplar and mahogany planks are often available in widths that permit a single plank to be used, just like the original alaias. Commercial alaia blanks of paulownia are also available (Visit woodsurfboardsupply.com. A local source for polar, cedar and mahogany is Yukon Lumber in Norfolk.

- Homemade blanks may need to be smoothed with either a hand plane, scraper, power planer or sander so that the blank has clean top and bottom faces and square edges. At this point, the blank resembles a thin, long rectangle of wood.

- After creating your blank, decide what your template (surfboard outline) should look like. Traditional alaias have round or oval noses that blend into parallel or tapered rails, the rails being the two long edges of the alaia blank. Normally templates are created to be a symmetrical mirror image of the full board and may be made of thin fiberboard, paper or cardboard. The shaper draws a center line down the length of the board and then traces the template outline on one side of the center line, flips the template over and the traces the template outline on the other side of the center line. An alternative is to make a nose template and then use the centerline technique and then to merge the nose shape into the rails.

- A saw is then used to cut out the template shape, normally leaving about a 1/4-inch margin to control for splintering. The cut edges are smoothed to the template shape with a hand plane or sander.

- A traditional alaia usually has a slightly convex top and bottom surface. One modification that is added is to have a convex curvature on the nose bottom that blends into the convex bottom and allows the alaia to drop down the face of a wave without burying the nose (pearling).

- Ancient alaias had curvatures that were shaped by eye and cut with stone tools. These curvatures can be also generated by using a modern router to cut a series of steps into the bottom and nose of the board, starting from the edge, where a deeper step is made and then working toward the center of the board with progressively more shallow steps. The depth and spacing of these steps determines the steepness of the bottom contour. These curvatures can also be created using sanders, wood files or power planers. The steps are then blended by sanding or planning to create a continuous curve. For example, a ¾ to 1-inch thick board bottom might start with a 3/8 inch step, then progress to 1/4-, 1/8- and 1/16-inch steps with possibly a flat section in the center. The top of the alaia may be flat, for a prone alaia or paipo, or slightly curved for a standup alaia (for this case, start with a 1/8-inch step and working inward). These curvatures can also be created using hand planes, sanders, spokeshaves, wood files/Microplanes™ or power planers.

- The rails can be left square, beveled or shaped to a so-called knife edge (traditional). The tail of the board is traditionally square.

- Once the alaia has been given a final sanding and cleaning with denatured alcohol, surface designs can be added via wood burning, carving or painting, or any combination of these or other techniques, although traditional boards were generally without artwork. The wood should then be treated to improve its durability and water-resistance. Wood treatments can be rubbing with oil (linseed oil is often used for modern alaias, although kukui oil was used for ancient alaias) or multiple coats of an exterior grade marine spar varnish designed for use below the waterline. Ancient alaias were also often submerged in clay soil for water proofing.