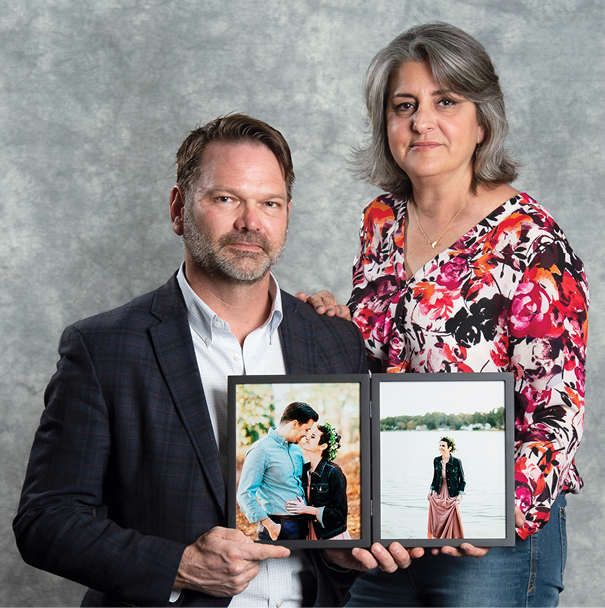

Dr. Galicia-Castillo learned that Abi had been reluctant to take her pain medications, fearing addiction and the feeling of being high and disconnected from the world. So she worked with Abi on a pain-management plan.

“Her pain was much better after that,” Mr. Rhoden says.

Abi never did go into hospice care, choosing to fight until she succumbed to her cancer last December.

“The oncologists extended her life,” Mr. Rhoden says, “but Dr. Galicia-Castillo made that extra life as good as it could possibly be.”

“What makes life meaningful enough to go on living?”

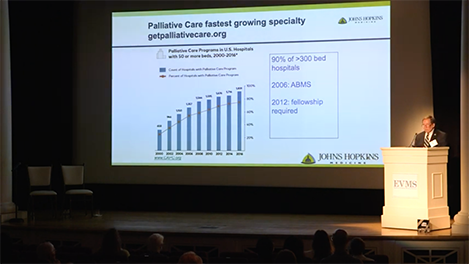

Thomas Smith, MD, is Director of Palliative Medicine for Johns Hopkins Medicine, as well as the Harry J. Duffey Family Professor of Palliative Care and Professor of Oncology for the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

A nationally known expert in palliative care, he was the guest speaker at a recent EVMS MedEd Talk on palliative medicine.

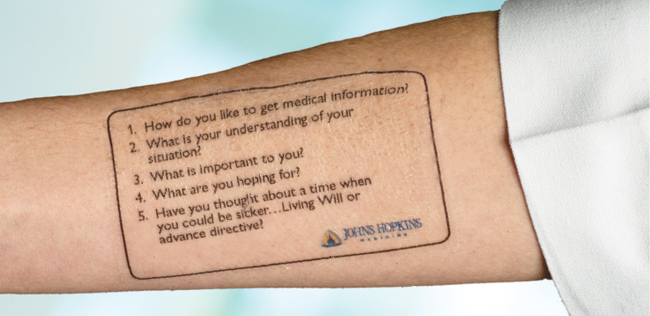

He’s also a tattoo artist — of sorts. “Every health professional should have primary palliative-care skills,” Dr. Smith says. As a reminder, he and his team created a temporary tattoo with these questions that he believes should be asked of every patient:

- How do you like to get medical information?

- What is your understanding of your situation?

- What is important to you?

- What are you hoping for?

- Have you thought about a time when you could be sicker — living will or advance directive?

“Then do the hardest thing in medicine,” Dr. Smith says. “Be quiet and listen.”

As for palliative medicine specialists, he explains that their first job is to find out who their patients are and how they fit into the world. So another question he suggests they ask: What gives you joy?

By reducing stress and pain, palliative care can help the patient medically. “The data are reasonably clear in oncology, where it’s been studied the most,” Dr. Smith says. “Symptoms are better controlled, quality of life is better and there’s less anxiety and depression.”

Bruce Waldholtz, MD, is living proof. A gastroenterologist, Dr. Waldholtz is Assistant Professor of Clinical Internal Medicine at EVMS, a member of the EVMS Board of Visitors — and a 19-year cancer survivor.

“Battling cancer helped me become a better doctor,” he says. And the palliative care he received back then sparked his interest in the field.

Today, as a board member of the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, Dr. Waldholtz advocates for the Palliative Care and Hospice Education Training Act. This federal legislation would fund an increase in the number of palliative-care faculty at schools of medicine, health professions and nursing around the nation.